Interfaith Marriage in Tunisia: A Clash of Court Opinions

Family law in Tunisia has been customarily viewed as an exception in the Arab world. It is distinctive in terms of consecrating civic principles into legal texts that regulate family-related institutions. One would thus assume that the answer to whether interfaith marriage is permissible by law is a clear Yes or No. However, it seems to be more complicated than that. One legal opinion held by some, the Yes view deems the marriage of a Muslim woman to a non-Muslim man, or of a Muslim man to a woman who is neither Muslim nor Christian nor Jewish (the latter two are referred to as people of the book), as legal. Another legal opinion, the No view, claims the exact opposite, namely, that the law permits it. Each view has theoretical justifications, and both disagree over which judicial rulings are relevant.

Advocates of the No view assert that Tunisian lawmakers adhered to the principles of Islamic law, and therefore outlawed marriage between a Muslim woman and a non-Muslim man or between a Muslim man and a woman who is neither Muslim, Christian or Jewish. Those who hold the opposite view say that Tunisian legislation is civil and does not distinguish between individuals on the basis of their beliefs; they accept interfaith marriage as a measure of freedom of belief. After considering both views, I suggest that legislative reform is needed to eliminate legal ambiguity pertaining to this question.

The No Camp: Tunisian Legislators Applied Islamic Law Principles in Setting the Conditions for Marriage

Although the Tunisian Code of Personal Status (CPS) contains no reference to religious differences as one of the obstacles to marriage as specified in Article 14[1], some interpreters of the law have clearly stated that a Muslim woman cannot marry a non-Muslim man and that a Muslim man cannot marry a woman who is neither Muslim, Christian or Jewish. They argue that the law’s stipulation that a marriage is valid only if no legal (Islamic law [shar’]) prohibitions exist, is a form of deferring to prohibitions of Islam, as defined by Islamic jurisprudence.[2] It follows that such jurisprudence applies, which thereby prevents a Muslim women from marrying a non-Muslim man and a Muslim man from marrying a woman who is neither Muslim, Christian or Jewish.

A decree by the Tunisian minister of justice dated November, 5,1973, which prohibits registrars and public notaries from concluding marriage contracts between Muslim women and non-Muslim men, is the most obvious evidence in favor of this view. Implementation of the decree obliged those who drafted marriage contracts to check [the couple’s religious identity] in advance, so as not to conclude marriages between Muslim women and non-Muslim men. Tunisian Muslim women were thus practically forbidden from marrying non-Muslim men in contracts concluded in Tunisia. On the other hand, marriages between Tunisian men and women of the book continued to be concluded in Tunisia, and marriages between Tunisian Muslim women and non-Muslim men could be concluded abroad. In the latter case, the contract could then be registered in the civil status records without the need -as required by the minister of justice's decree- for the husband to publicly convert to Islam in front of Tunisia's chief mufti [religious cleric].

Pro-Islamic law courts consider such marriages invalid and call for their public annulment. In this regard, a significant number of judges in the provinces insist on refusing to include foreigners who cannot prove they are Muslims in the list of heirs when their family relative dies. This enforces the ban on marriage by refusing to recognize the consequence of such a marriage. It is worth noting that when it comes to inheritance the ban is stricter because it does not distinguish between, on the one hand, women of the book who have been married to Muslim men and, on the other hand, other women. It prevents all non-Muslims from inheriting from Muslims and it prevents Muslim family members from bequeathing assets to their non-Muslim descendants.

The pro-Islamic law viewpoint was the dominant one since the Code of Personal Status was published in 1957 until the beginning of 2000. The opposite position, however, began to gain the upper hand during the past decade.

The Yes Camp: Tunisian Law Prohibits Belief-Based Discrimination

Advocates of this view maintain that those who call for banning interfaith marriages are imposing their doctrinal views on Tunisian law, rather than applying it. They are refusing to implement the law on the pretext that the legal texts need to be interpreted. Members of the Yes camp explain that Tunisian law outlines all forms of religious discrimination. It does not require the indication of religious identity in personal status documents, and it outlaws any reference to the beliefs of individuals as per the Data Protection Act. Moreover, the law does not mention religion as an impediment to marriage or to inheritance. Courts of the Yes camp have stressed that the choosing of one's spouse is a fundamental right, and pointed out Tunisia’s ratification of international conventions, especially the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).[3]

Although a significant proportion of jurists are inclined to adopt the Yes view, the influence of the No camp has not receded completely. The ministerial decree that prohibits marriages between a Muslim woman and a non-Muslim man remains in force. Civil status officers enforce it strictly, and judges in the provinces are careful not to include the names of foreign women that suggest they are not Muslims on the list of the names of heirs when Tunisians die.

The judiciary appears to be divided over the legality of a Muslim woman marrying a non-Muslim man. Most legal rulings show that the courts are inclined not to take difference of belief as a reason to invalidate a marriage, and to consequently deny inheritance rights to non-Muslims. There are, however, judicial rulings that continue to uphold the marriage ban and to deny inheritance rights to foreign partners who do not hold Muslim names, and are unable to prove their Muslim identity by providing an official certificate from the office of the mufti. These rulings also deny inheritance rights to the children of such partners.

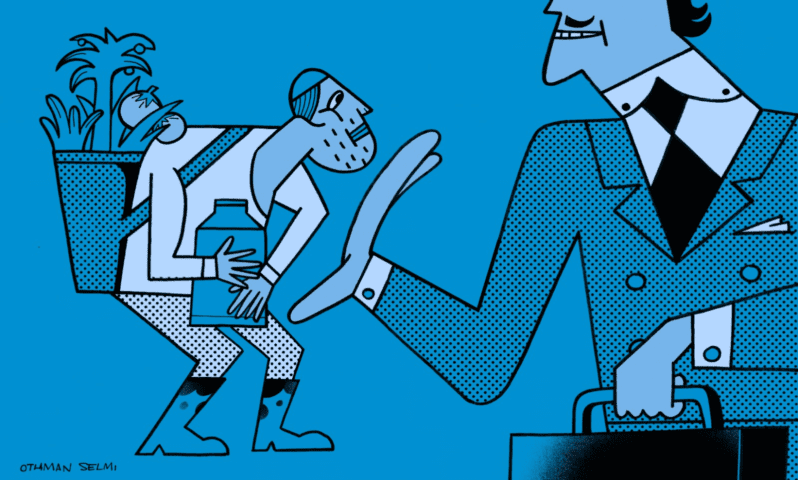

These contradictions show the depth of the cultural problem posed by the Tunisian Code of Personal Status in more than half a century after its introduction. Attempts by segments of the judiciary, the civil service, and some law experts to prohibit interfaith marriages are a sign of their resistance to trends they see as incompatible with established norms in society, and a threat to the latter’s [cultural] specificity. This school of thought has had significant success. The emergence in the last decade or so of a rival and increasingly dominant trend that seeks to impose secular or civil values on family relationships is an important development. Such an emergence will definitely be strengthened by the new Tunisian Constitution, which upholds in Article 21 the principle of equality before the law without discrimination, as well as the right to freedom of conscience.

In order to prevent those who implement the law from getting influenced by their intellectual and ideological convictions, this legal dispute must be resolved. Calling on the Ministry of Justice to take an official position on whether the ministerial decree of November 5, 1973 remains in force, is a start.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

__________

[1] Article 14 of the Code of Personal Status states: “impediments to marriage fall into two categories: permanent and temporary. The permanent impediments are ‘close relationship by blood, by marriage or through being breastfed by the same mother, or by irrevocable divorce’. The temporary impediments include the existence of other marital obligations or the fact that the woman is still in the idda period after a divorce or the death of a husband.”

[2] Professor al-Hadi Kirru expressed this position: “The absence of legal impediments is an overall prerequisite for all the attributes that the couple must fulfill.”

[3] Civil Appeal Decision No. 31115, dated February 5, 2009: “Guaranteeing women's right to marry on an equal footing with men, as enshrined in paragraph 1(b) of Article 16, makes it impossible to argue that a woman's beliefs should have any effect on her freedom to marry.”